Le glioblastome est la tumeur cérébrale maligne la plus courante. Elle provient des cellules de soutien du cerveau, peut se produire n'importe où dans le cerveau et touche généralement les personnes âgées de 50 à 70 ans. La thérapie standard est une combinaison de chirurgie, de radiothérapie et de chimiothérapie (le régime dit de Stupp). Cependant, le terme «thérapie standard» ne décrit pas ce qui est nécessaire pour maximiser la survie du patient. Notre préoccupation ne se limite pas à la norme.

Neurochirurgie Inselspital - nos chiffres et faits

- Excellence : des neurochirurgiens hautement spécialisés et des infirmières en oncologie spécialement formées (Advanced Practice Nurses ou APN en abrégé)

- Expertise : 447 opérations de tumeurs (biopsies et résections) en 2023, dont 322 gliomes.

- Équipe interdisciplinaire : notre tumor board hebdomadaire réunit des spécialistes de 7 disciplines - neurochirurgie, neurologie, neuroradiologie, oncologie, médecine nucléaire, radio-oncologie, pathologie.

- Développé et étudié à l'Inselspital : techniques de neuromonitoring et de navigation innovantes pour la sécurité des opérations et la prévention des déficits.

- Taux de déficits parmi les plus bas au monde : le taux documenté et publié de 3 à 5 % de déficits permanents liés à l'opération pour les tumeurs à risque d'éloquence motrice est l'un des plus bas au monde !

- Taux de résection parmi les plus élevés au monde : le taux de résection complète > 90 % pour les gliomes est l'un des plus élevés au monde !

- Équipement technologique de pointe avec imagerie peropératoire, techniques de fluorescence, thermothérapie au laser et plus encore.

- Concept de traitement complémentaire : notre protocole OPTIMISST (OPTIMISST signifie Optimized Standard and Supportive Therapy).

- Certification : centre certifié pour les tumeurs cérébrales depuis 2016, garant d'une norme de qualité élevée dans le traitement oncologique.

Pourquoi faut-il recourir à une chirurgie radicale en cas de glioblastome?

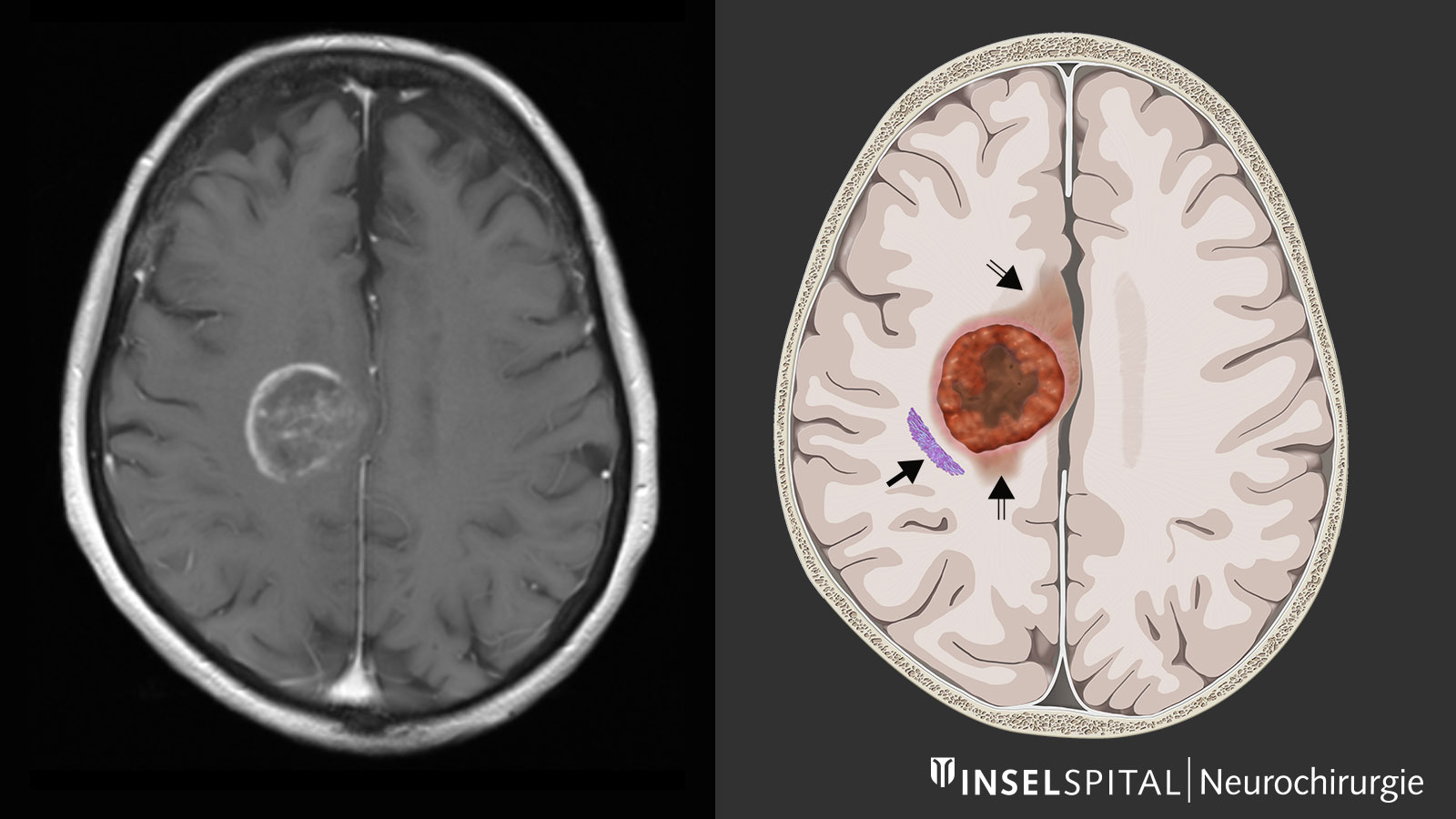

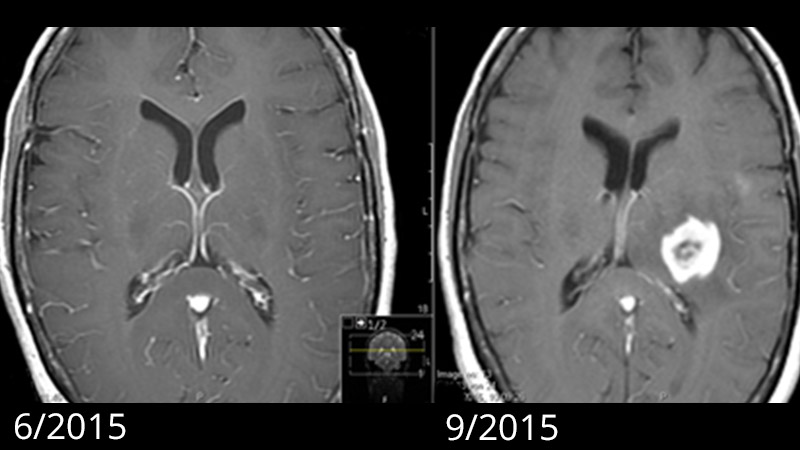

Bien qu'il y ait déjà un avantage en termes de survie lorsque 80 % d'un glioblastome est retiré ou qu'il reste moins de 5 cm3 de tumeur, seule l'élimination à 100 % sans reste de tumeur détectable à l'IRM permet d'obtenir une amélioration maximale de la survie. Par conséquent, l'objectif premier de la chirurgie devrait être l'ablation complète de la tumeur cérébrale, idéalement en incluant la zone d'infiltration visible sur l'image IRM, et ce sans causer de dommages neurologiques permanents.

Seule une opération chirurgicale sans complications neurologiques présente des avantages

Les avantages de la chirurgie radicale en cas de glioblastome ne s'appliquent que si on peut éviter une paralysie permanente, des troubles de la parole ou d'autres dommages graves. Sinon, le temps de survie diminue à nouveau (McGirt 2009 *). La surveillance fonctionnelle spécialisée - la surveillance neurophysiologique - est destinée à prévenir les dommages liés à la chirurgie et constitue dans de nombreux cas l'outil intra-opératoire le plus important et une spécialité de notre clinique. À l'Inselspital, nous avons développé une cartographie dynamique continue basée sur un radar à petites impulsions de courant, qui détecte la fonction de mouvement. Cette procédure est maintenant utilisée dans plus de 50 pays dans le monde.

Le traitement des tumeurs cérébrales est un point central de notre clinique avec une équipe de neurochirurgie spécialisée dans les tumeurs composée de 6 médecins, des infirmières en oncologie supplémentaires (Advanced Practice Nurses), des salles d'opération équipées des dernières technologies médicales, y compris l'imagerie peropératoire et des techniques de neuromonitoring et de navigation hautement spécialisées.

Les taux de réussite publiés par le service de neurochirurgie de l'Inselspital pour l'exérèse complète des tumeurs selon les critères de l'IRM tout en évitant les dommages neurologiques graves sont parmi les plus élevés au monde.

Centre certifié pour les tumeurs cérébrales

À l'Inselspital, la meilleure stratégie de traitement possible est définie individuellement pour chaque patient. Cela se fait dans le centre certifié des tumeurs cérébrales, où une équipe interdisciplinaire discute et détermine toutes les options thérapeutiques individuellement pour chaque patient.

Ce tumor board hebdomadaire se compose de spécialistes en neurochirurgie, neurologie, neuro-oncologie, médecine nucléaire, radio-oncologie et pathologie.

Notre protocole OPTIMISST complète le traitement standard

Il existe toute une série de facteurs qui contribuent à une thérapie tumorale plus efficace et constituent ainsi un complément précieux au traitement standard. Les objectifs sont les suivants

- une récupération plus rapide de nos patients

- un séjour plus court à l'hôpital

- une plus grande autonomie du patient

- une plus grande sécurité lors du traitement

- une meilleure qualité de vie

- un effet positif sur le contrôle de la tumeur

Nous avons développé à l'Inselspital un protocole de traitement qui tient compte de tous ces facteurs positifs: le protocole dit OPTIMISST. OPTIMISST signifie «OPTIMIzed Standard and Supportive Therapy».

Incidence et groupes à risque

Les glioblastomes apparaissent généralement chez les adultes âgés (50-85 ans), l'âge moyen étant de 64 ans *. Les glioblastomes peuvent apparaître chez les enfants mais ne représentent que 2,9 % de toutes les tumeurs cérébrales de la tranche d'âge 0-19 ans *. Dans l'ensemble, il s'agit de tumeurs rares, avec environ 3–4 nouveaux diagnostics par an pour 100 000 habitants *. Les hommes ont 1,5 fois plus de chances d'être touchés que les femmes.

Les causes du développement du glioblastome

Le seul facteur de risque confirmé pour le développement d'un glioblastome est une irradiation antérieure de la tête. Une association avec un traumatisme crânien antérieur, des toxines ou un régime alimentaire n'a pas pu être clairement démontrée *, *. Les facteurs héréditaires ne jouent qu'un rôle mineur. Il est intéressant de noter que les patients souffrant de maladies allergiques (asthme, dermatite atopique, allergies alimentaires, etc.) sont considérés comme ayant un risque plus faible de développer un glioblastome *.

De nouvelles hypothèses suggèrent que la première cellule de glioblastome peut se développer jusqu'à 7 ans avant le diagnostic. Selon cette hypothèse, les mutations précoces et critiques de la tumorigenèse se produisent 2 à 7 ans avant le diagnostic. Cependant, c'est l'apparition de mutations supplémentaires qui déclenche ensuite la croissance rapide typique du glioblastome. Les patients dont l'IRM était auparavant sans grande particularité savent que le glioblastome visible à l'imagerie s'est rapidement développé en quelques mois *, *.

-

McGirt MJ, Mukherjee D, Chaichana KL, Than KD, Weingart JD, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Association of surgically acquired motor and language deficits on overall survival after resection of glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:463-470.

-

Pitter KL, Tamagno I, Alikhanyan K et al. Corticosteroids compromise survival in glioblastoma. Brain. 2016;139:1458-1471.

-

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2009-2013. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:v1-v75.

-

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, de Blank PM et al. American brain tumor association adolescent and young adult primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012. Neuro-oncology. 2016;18:i1-i50.

-

Lahkola A, Auvinen A, Raitanen J et al. Mobile phone use and risk of glioma in 5 North European countries. International journal of cancer. 2007;120:1769-1775.

-

Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:896-913.

-

Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555:469-474.

-

Soffietti R, Baumert BG, Bello L et al. Guidelines on management of low-grade gliomas: report of an EFNS-EANO Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1124-1133.

-

Inskip PD, Tarone RE, Hatch EE et al. Cellular-telephone use and brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:79-86.

-

Pedersen CL, Romner B. Current treatment of low grade astrocytoma: a review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1-8.

-

Claus EB, Black PM. Survival rates and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with supratentorial low-grade gliomas: data from the SEER program, 1973-2001. Cancer. 2006;106:1358-1363.

-

Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492-507.

-

Mintz A, Perry J, Spithoff K, Chambers A, Laperriere N. Management of single brain metastasis: a practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2007;14:131-143.

-

Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:494-500.

-

Jakola AS, Skjulsvik AJ, Myrmel KS et al. Surgical resection versus watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1942-1948.

-

Sanai N, Polley MY, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Berger MS. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:3-8.

-

Sanai N, Berger MS. Extent of resection influences outcomes for patients with gliomas. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2011;167:648-654.

-

Cancer GARN. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061-1068.

-

Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:190-198.

-

Salvati M, Pichierri A, Piccirilli M et al. Extent of tumor removal and molecular markers in cerebral glioblastoma: a combined prognostic factors study in a surgical series of 105 patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 2012;117:204-211.

-

Capelle L, Fontaine D, Mandonnet E et al. Spontaneous and therapeutic prognostic factors in adult hemispheric World Health Organization Grade II gliomas: a series of 1097 cases. Journal of neurosurgery. 2013;118:1157-1168.

-

McGirt MJ, Chaichana KL, Attenello FJ et al. Extent of surgical resection is independently associated with survival in patients with hemispheric infiltrating low-grade gliomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:700-7; author reply 707.

-

Bloch O, Han SJ, Cha S et al. Impact of extent of resection for recurrent glioblastoma on overall survival: clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:1032-1038.

-

Chaichana KL, Cabrera-Aldana EE, Jusue-Torres I et al. When gross total resection of a glioblastoma is possible, how much resection should be achieved. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:e257-65.

-

Keles GE, Lamborn KR, Berger MS. Low-grade hemispheric gliomas in adults: a critical review of extent of resection as a factor influencing outcome. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:735-745.

-

Oppenlander ME, Wolf AB, Snyder LA et al. An extent of resection threshold for recurrent glioblastoma and its risk for neurological morbidity. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:846-853.

-

Schucht P, Murek M, Jilch A et al. Early re-do surgery for glioblastoma is a feasible and safe strategy to achieve complete resection of enhancing tumor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79846.

-

Schucht P, Knittel S, Slotboom J et al. 5-ALA complete resections go beyond MR contrast enhancement: shift corrected volumetric analysis of the extent of resection in surgery for glioblastoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156:305-12; discussion 312.

-

Gill BJ, Pisapia DJ, Malone HR et al. MRI-localized biopsies reveal subtype-specific differences in molecular and cellular composition at the margins of glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12550-12555.

-

Jain R, Poisson LM, Gutman D et al. Outcome prediction in patients with glioblastoma by using imaging, clinical, and genomic biomarkers: focus on the nonenhancing component of the tumor. Radiology. 2014;272:484-493.

-

Yordanova YN, Moritz-Gasser S, Duffau H. Awake surgery for WHO Grade II gliomas within “noneloquent” areas in the left dominant hemisphere: toward a “supratotal” resection. Journal of neurosurgery. 2011

-

Gil-Robles S, Duffau H. Surgical management of World Health Organization Grade II gliomas in eloquent areas: the necessity of preserving a margin around functional structures. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E8.

-

Duffau H. Is supratotal resection of glioblastoma in noneloquent areas possible. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:e101-3.

-

Ius T, Angelini E, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Mandonnet E, Duffau H. Evidence for potentials and limitations of brain plasticity using an atlas of functional resectability of WHO grade II gliomas: towards a “minimal common brain”. Neuroimage. 2011;56:992-1000.

-

Duffau H, Taillandier L. New concepts in the management of diffuse low-grade glioma: Proposal of a multistage and individualized therapeutic approach. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:332-342.

-

De Witt Hamer PC, Robles SG, Zwinderman AH, Duffau H, Berger MS. Impact of intraoperative stimulation brain mapping on glioma surgery outcome: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2559-2565.

-

Duffau H, Capelle L, Denvil D, et al. Usefulness of intraoperative electrical subcortical mapping during surgery for low-grade gliomas located within eloquent brain regions: functional results in a consecutive series of 103 patients. J Neurosurg 2003;98:764-78.

-

Duffau H, Peggy Gatignol ST, Mandonnet E, Capelle L, Taillandier L. Intraoperative subcortical stimulation mapping of language pathways in a consecutive series of 115 patients with Grade II glioma in the left dominant hemisphere. J Neurosurg 2008;109:

-

Keles GE, Lundin DA, Lamborn KR, Chang EF, Ojemann G, Berger MS. Intraoperative subcortical stimulation mapping for hemispherical perirolandic gliomas located within or adjacent to the descending motor pathways: evaluation of morbidity and assessment of functional outcome in 294 patients. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:369-375.

-

Raabe A, Beck J, Schucht P, Seidel K. Continuous dynamic mapping of the corticospinal tract during surgery of motor eloquent brain tumors: evaluation of a new method. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:1015-1024.

-

Chacko AG, Thomas SG, Babu KS et al. Awake craniotomy and electrophysiological mapping for eloquent area tumours. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:329-334.

-

Spena G, Garbossa D, Panciani PP, Griva F, Fontanella MM. Purely subcortical tumors in eloquent areas: awake surgery and cortical and subcortical electrical stimulation (CSES) ensure safe and effective surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1595-1601.

-

Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T et al. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:392-401.

-

Stummer W, Stocker S, Wagner S et al. Intraoperative detection of malignant gliomas by 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrin fluorescence. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:518-25; discussion 525.

-

Pogue BW, Gibbs-Strauss S, Valdés PA, Samkoe K, Roberts DW, Paulsen KD. Review of Neurosurgical Fluorescence Imaging Methodologies. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2010;16:493-505.

-

Hebeda KM, Saarnak AE, Olivo M, Sterenborg HJ, Wolbers JG. 5-Aminolevulinic acid induced endogenous porphyrin fluorescence in 9L and C6 brain tumours and in the normal rat brain. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:503-12; discussion 512.

-

Schucht P, Beck J, Abu-Isa J et al. Gross total resection rates in contemporary glioblastoma surgery: results of an institutional protocol combining 5-aminolevulinic acid intraoperative fluorescence imaging and brain mapping. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:927-35; discussion 935.

-

Louvel G, Metellus P, Noel G, et al. Delaying standard combined chemoradiotherapy after surgical resection does not impact survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. Radiother Oncol 2016;118:9-15.

-

Loureiro LV, Victor ES, Callegaro-Filho D et al. Minimizing the uncertainties regarding the effects of delaying radiotherapy for Glioblastoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:1-8.

-

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987-996.

-

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:459-66.

-

Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:709-722.

-

Schäfer N, Proescholdt M, Steinbach JP et al. Quality of life in the GLARIUS trial randomizing bevacizumab/irinotecan versus temozolomide in newly diagnosed, MGMT-nonmethylated glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:975-985.

-

Blumenthal DT, Gorlia T, Gilbert MR et al. Is more better? The impact of extended adjuvant temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a secondary analysis of EORTC and NRG Oncology/RTOG. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:1119-1126.

-

Gilbert MR, Wang M, Aldape KD et al. Dose-dense temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4085-4091.

-

Herrlinger U, Tzaridis T, Mack F et al. Lomustine-temozolomide combination therapy versus standard temozolomide therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CeTeG/NOA-09): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:678-688.

-

Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:707-715.

-

Perry JR, Laperriere N, O’Callaghan CJ et al. Short-Course Radiation plus Temozolomide in Elderly Patients with Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1027-1037.

-

Weller M, Butowski N, Tran DD et al. Rindopepimut with temozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma (ACT IV): a randomised, double-blind, international phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1373-1385.

-

Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:150-161.

-

Lang FF, Conrad C, Gomez-Manzano C et al. Phase I Study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) Oncolytic Adenovirus: Replication and Immunotherapeutic Effects in Recurrent Malignant Glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1419-1427.

-

Mitchell LA, Lopez Espinoza F, Mendoza D et al. Toca 511 gene transfer and treatment with the prodrug, 5-fluorocytosine, promotes durable antitumor immunity in a mouse glioma model. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:930-939.

-

Reulen HJ, Poepperl G, Goetz C et al. Long-term outcome of patients with WHO Grade III and IV gliomas treated by fractionated intracavitary radioimmunotherapy. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:760-770.

-

Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner AA et al. Maintenance Therapy With Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Temozolomide vs Temozolomide Alone for Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2535-2543.

-

Weller M, Tabatabai G, Kästner B et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation Is a Strong Prognostic Biomarker for Benefit from Dose-Intensified Temozolomide Rechallenge in Progressive Glioblastoma: The DIRECTOR Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2057-2064.

-

Gately L, McLachlan SA, Philip J, Ruben J, Dowling A. Long-term survivors of glioblastoma: a closer look. J Neurooncol. 2018;136:155-162.

-

Krex D, Klink B, Hartmann C et al. Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain. 2007;130:2596-2606.

-

Reifenberger G, Weber RG, Riehmer V et al. Molecular characterization of long-term survivors of glioblastoma using genome- and transcriptome-wide profiling. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1822-1831.

-

Archibald YM, Lunn D, Ruttan LA et al. Cognitive functioning in long-term survivors of high-grade glioma. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:247-253.

-

Steinbach JP, Blaicher HP, Herrlinger U et al. Surviving glioblastoma for more than 5 years: the patient’s perspective. Neurology. 2006;66:239-242.

-

Bähr O, Herrlinger U, Weller M, Steinbach JP. Very late relapses in glioblastoma long-term survivors. J Neurol. 2009;256:1756-1758.