Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), formerly also known as pseudotumor cerebri, is a rare and often unrecognized disorder. The main clinical symptoms are usually chronic headaches and visual disturbances. These symptoms are due to increased intracranial pressure for which no organic cause can be found. Thanks to modern neurosurgery and neuroradiology, various treatment options are now available for this rare condition.

How common is idiopathic intracranial hypertension?

IIH is a rare disease that occurs with a frequency of 1–21 per 100,000 inhabitants. Women in the third decade of life are most frequently affected. Hormonal influences seem to play an important and still unknown role. Pregnancy is therefore also considered a risk factor. In 37% of all cases, children are affected – boys and girls equally. Of these, 90% are between the ages of 5 and 15.

What are the symptoms of idiopathic intracranial hypertension?

IIH can cause numerous different symptoms that are consistent with those of a brain tumor.

The most common symptoms are:

- headaches

- dizziness

- nausea

- visual disturbances (blurred vision, double vision, visual field restrictions)

In contrast to a cerebrospinal fluid leak, the headaches are worse when lying down.

Damage to the optic nerve can result in anything from slight impairment of visual acuity and the visual field to complete constriction of the visual field or even blindness, which is the case in up to 12% of patients. Irritation of the abducens nerve can also cause double vision as a symptom.

Furthermore, some patients also describe pulse-synchronized tinnitus as well as eye or neck pain or neck stiffness.

The symptoms can increase both gradually and very quickly and are usually nonspecific, which is why they are often initially misdiagnosed.

What is the cause of idiopathic intracranial hypertension?

As the name suggests, the causes of IIH are largely unknown. In theory, the condition is attributed to mechanical obstruction of the venous return flow from the head. Triggering factors could be overweight (obesity in 11–90% of those affected) or an overproduction of cerebrospinal fluid.

Epidemiological studies have investigated various factors that could be associated with the occurrence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The influences listed at the top of the list below are considered to be very probable and then decrease in probability downwards:

- overweight

- chemical substances (ketones, lindane)

- vitamin A overdose

- discontinuation of steroids

- thyroxine administration in children

- hypoparathyroidism

- Addison's crisis

- uremia

- iron deficiency anemia

- medication (tetracyclines, danazol, lithium, tamoxifen, amiodarone, phenytoin, ciprofloxacin, etc.)

- menstrual irregularities

- oral contraceptives

- Cushing syndrome

- vitamin A deficiency

- mild traumatic brain injury

- Behçet disease

- hyperthyroidism

- steroid use

- vaccinations

- pregnancy

- menarche

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- otitis media with skull base involvement

- radical tumor operations in the neck area

Sinus or cerebral venous thrombosis are also frequently associated with the disease. To what extent it is a cause or consequence of the increased intracranial pressure is not yet clear. In these cases, endovascular interventions with dilatation and stenting may be a therapeutic option.

How is idiopathic intracranial hypertension diagnosed?

The idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a diagnosis of exclusion. This means that one looks for structural causes for the increased intracranial pressure. A first indication of IIH arises from the clinical complaints and the patient's medical history, taking into account the mentioned risk factors. If no reason for the increrased intracranial pressure is found in the investigation, the diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension can be established.

Clinical examination

The clinical examination often reveals an unremarkable neurological status. In affected patients, an eye examination must be performed due to the risk of a bilateral congestive papilledema. Less common are unilateral or bilateral paralysis of the abducens nerve, a reduction in visual acuity or visual field. Furthermore, a laboratory-chemical pituitary insufficiency with an inadequate response to pituitary stimulation can be detected.

Imaging

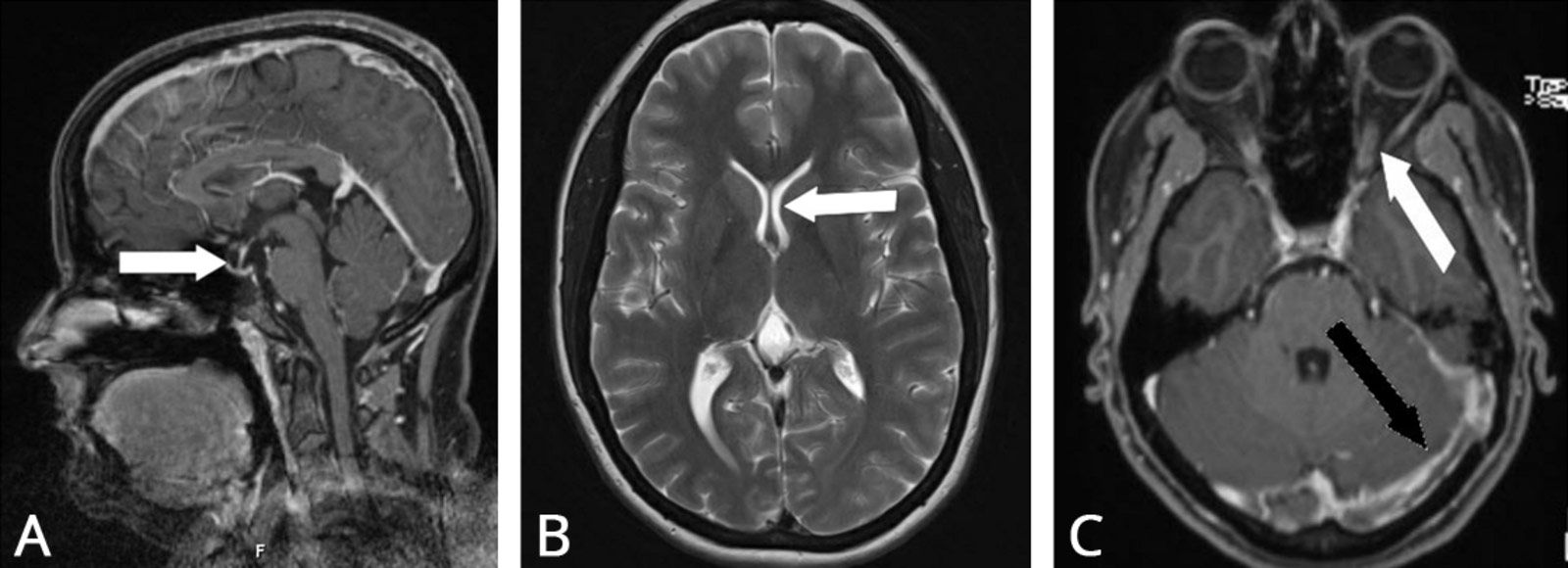

Cranial imaging using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to rule out hydrocephalus, an intracranial mass or other pathologies as the cause of the increased intracranial pressure. There is no sufficiently reliable diagnostic imaging criterion for IIH on its own. MRI imaging usually only provides non-specific findings.

Thromboses of the draining cerebral veins are also repeatedly described. The extent to which these are the cause or the consequence of increased intracranial pressure has not yet been clarified. Therefore, cerebral angiography of the vessels supplying the brain may also be necessary if sinus vein thrombosis is detected.

Lumbar puncture

After the clinical examination and imaging, a lumbar puncture is performed. Firstly, the opening pressure is measured, which is classified as increased from a value of 20–25 cm H2O, and secondly, laboratory tests of the cerebrospinal fluid are arranged.

How is idiopathic intracranial hypertension treated?

The treatment options for IIH are applied in a stepwise escalation, depending on the severity of the symptoms. Spontaneous improvement of symptoms often occurs within a year, even though signs of papilledema may persist in follow-up examinations for a longer period.

Depending on the nature of the symptoms at the initial diagnosis, an individualized treatment strategy must be determined and adjusted according to the course of the disease. The Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) recommends a stepwise approach:

IIH without neurological deficits

For mild symptoms (headaches without visual disturbances), conservative treatment is primarily recommended. Potential triggers of idiopathic intracranial hypertension must be identified to counteract them. Fundamental for sustained therapeutic success is always consistent and long-term weight reduction. Additionally, the medication acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, can be taken to reduce cerebrospinal fluid production. An alternative is topiramate (another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor), which also leads to weight reduction. If necessary, furosemide (a diuretic) may be used additionally to eliminate excess body water.

IIH with moderate neurological deficits

In case of reduced visual acuity, which, however, progresses without rapid deterioration, a therapeutic lumbar puncture is performed in addition to the measures mentioned above. During this procedure, several milliliters of cerebrospinal fluid are drained to immediately lower intracranial pressure. Symptoms improve in a quarter of patients after the first puncture. The puncture is repeated at short intervals and, as symptoms improve, at longer intervals until the therapy can be concluded.

Only in cases where repeated lumbar punctures cannot be stopped due to persistent or increasing symptoms, a permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion must be surgically implemented. There are several surgical procedures for this:

- The most common procedure is the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

- Less common alternatives include the lumboperitoneal diversion from the spinal cerebrospinal fluid channel to the abdominal cavity or from the ventricle to the atrium of the heart.

- If weight reduction is insufficient, considering obesity surgery is advisable.

IIH with severe and/or rapidly progressive neurological deficits

In case of rapid deterioration of visual acuity or the visual field, prompt action is required. Intracranial pressure must be consistently reduced. If conservative treatment does not bring immediate improvement in symptoms, a surgical approach must be considered. In addition to the shunting of cerebrospinal fluid mentioned above, there is the option of microsurgical fenestration of the optic nerve sheath. This leads to immediate pressure relief and nerve recovery. This procedure is only necessary in very rare cases.

Novel experimental treatments

In 2002, Higgins et al. * published a new procedure: the first catheter-based intervention in the form of sinus stenting in a patient with bilateral distal transverse sinus stenoses that were not treatable with conventional methods. The intervention resulted in a significant improvement of symptoms. However, this method is not considered a standard procedure for IIH and is only applied in very carefully selected patients, exclusively in specialized centers such as Inselspital. There is limited data available on success rates and long-term outcomes so far.

IIH without neurological deficits

For mild symptoms (headaches without visual disturbances), conservative treatment is primarily recommended. Potential triggers of idiopathic intracranial hypertension must be identified to counteract them.

Fundamental for sustained therapeutic success is always consistent and long-term weight reduction. Additionally, the medication acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, can be taken to reduce cerebrospinal fluid production. An alternative is topiramate (another carbonic anhydrase inhibitor), which also leads to weight reduction. If necessary, furosemide (a diuretic) may be used additionally to eliminate excess body water.

IIH with moderate neurological deficits

In case of reduced visual acuity, which, however, progresses without rapid deterioration, a therapeutic lumbar puncture is performed in addition to the measures mentioned above. During this procedure, several milliliters of cerebrospinal fluid are drained to immediately lower intracranial pressure. Symptoms improve in a quarter of patients after the first puncture. The puncture is repeated at short intervals and, as symptoms improve, at longer intervals until the therapy can be concluded.

Only in cases where repeated lumbar punctures cannot be stopped due to persistent or increasing symptoms, a permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion must be surgically implemented. There are several surgical procedures for this:

- The most common procedure is the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

- Less common alternatives include the lumboperitoneal diversion from the spinal cerebrospinal fluid channel to the abdominal cavity or from the ventricle to the atrium of the heart.

- If weight reduction is insufficient, considering obesity surgery is advisable.

IIH with severe and/or rapidly progressive neurological deficits

In case of rapid deterioration of visual acuity or the visual field, prompt action is required. Intracranial pressure must be consistently reduced. If conservative treatment does not bring immediate improvement in symptoms, a surgical approach must be considered. In addition to the shunting of cerebrospinal fluid mentioned above, there is the option of microsurgical fenestration of the optic nerve sheath. This leads to immediate pressure relief and nerve recovery. This procedure is only necessary in very rare cases.

Novel experimental treatments

In 2002, Higgins et al * published a new procedure: the first catheter-based intervention in the form of sinus stenting in a patient with bilateral distal transverse sinus stenoses that were not treatable with conventional methods. The intervention resulted in a significant improvement of symptoms. However, this method is not considered a standard procedure for IIH and is only applied in very carefully selected patients, exclusively in specialized centers such as Inselspital. There is limited data available on success rates and long-term outcomes so far.

What is the prognosis for idiopathic intracranial hypertension?

As there are various treatment options for IIH, the measures and guidelines must be individually tailored to the patient and discussed in detail with them.

In general, our patients can be mobilized quickly after each treatment and stay in the hospital for observation for only a few days. Depending on the clinical condition, discharge home is possible. If neurological impairments are present, rehabilitation should be considered in consultation with the patient.

In approximately 10% of cases, there may be a recurrence of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Permanent loss of vision can be prevented in 76–98% of patients. Persistent headaches may occur in some individuals.

Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:488-494.

Kanagalingam S, Subramanian PS. Cerebral venous sinus stenting for pseudotumor cerebri: A review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29:3-8.

Wong R, Madill SA, Pandey P, Riordan-Eva P. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the association between weight loss and the requirement for systemic treatment. BMC Ophthalmol. 2007;7:15.

-

Higgins JN, Owler BK, Cousins C, Pickard JD. Venous sinus stenting for refractory benign intracranial hypertension. Lancet. 2002;359:228-230.